Entoyment Wargaming and Hobby Centre

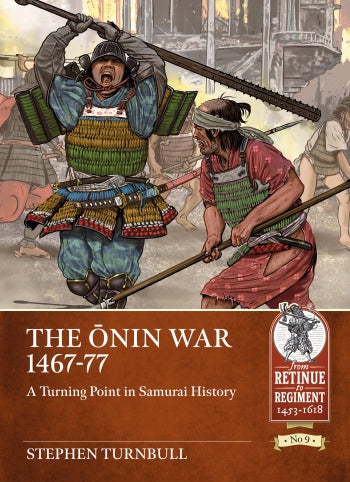

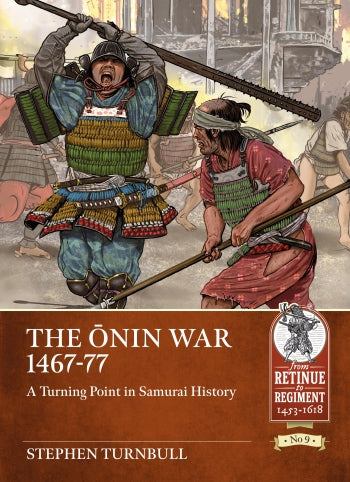

The Onin War 1467-77

The Onin War 1467-77

Out of stock

Couldn't load pickup availability

Out Of Stock!

We will notify you when this product becomes available.

The story of the terrible Ōnin War has now been told. In this ground breaking book the author has drawn on previously untranslated primary sources to set the famous yet misunderstood conflict in its true context. Its history begins with the glory days of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu who made the position of shogun into something that was admired and respected, and left a legacy symbolised by his famous Golden Pavilion.

Within decades all that he had achieved seemed to have been lost. In 1441 the reigning shogun Yoshinori, Yoshimitsu’s son, had been murdered by a jealous rival. The Bakufu (shogunate) had somehow survived, but Yoshinori was succeeded first by a son who never reached manhood and then by another young son called Yoshimasa. He was to reign for 49 years in a turbulent age. Not only did Yoshimasa have to face up to his background of family tragedy; unprecedented waves of rioting by farmers shook the ruling classes as much as any wars could have done, and all this happened to a background of famines, droughts and floods that killed more people than any of the battles ever did.Yoshimasa had several armed conflicts to contend with, which culminated in a succession dispute over his own choice of heir. This launched the Ōnin War.

There had been conflicts before, but what made the Ōnin War unique was the fierce street-fighting that went on within Kyoto itself. The battles were conducted from fortified mansions, which were surrounded by stout wooden walls and ditches and sported tall observation towers. In one such fight in the summer of 1467 eight cartloads of heads were taken as trophies, but within months the conflict deteriorated into a stalemate where night raids were launched and large stones were flung by catapult. At the same time huge areas of Kyoto were needlessly burned out by careless attacks from irregular troops called ashigaru, whose looting and destruction went far beyond the enemy positions and took in temples, mansions, and commoners’ dwellings.

The greatest loss of all was the disappearance of loyalty to the shogun. Instead, his former deputies in the provinces seized power in their local areas. This was the beginning of the Sengoku Period: Japan’s ‘Age of Warring States’. The book ends with one of these sengoku daimyo (lords of the warring states) called Hōjō Sōun, whose family would control much of Eastern Japan for the next century, owing nothing to the authority of the shogun, whose powers had been taken away by the terrible Ōnin War.

Share